Archive for March, 2013

Friday, March 22nd, 2013

Like the giant statue that supposedly straddled the mouth of the harbour at Rhodes in ancient times, Peter Fulton doesn’t move his feet much.

The six-foot-five batsman, the man they call “Two-Metre Peter”, drafted back into the New Zealand side for this series after a period of over three years away from the Test arena, had a typically nervy start to his innings.

Rather than qualifying as one of the seven wonders of the world, his technique is such that you spend the first hour of his innings wondering why the hell he hasn’t gotten out yet. The feet are resolutely planted; balls wide of off-stump are wafted at with shots that constitute neither attack nor defence, with a lot of daylight visible between bat and body – enough space that you could sail a fleet of triremes through if you were an opportunistic invader intent on plunder. This is how he got out at Wellington and Dunedin, back in his crease and poking at deliveries he really should have left alone.

He is the complete opposite of his opening partner, Hamish Rutherford – broad-shouldered and heavy-footed where Rutherford is wiry and nimble, with an almost lumbering rigidity in contrast to Rutherford’s fluid economy of movement. Certainly Rutherford makes more pleasing shapes when batting – the way he leant into a beautiful drive down the ground off Jimmy Anderson, all crisp timing and high right elbow, was a particularly memorable example. Rutherford might have talent in spades but, in a similar vein to his captain, Brendon McCullum, he is also a scrapper, and has the bruises to prove it.

Fulton goes about his business in quieter fashion, a slight frown on his face that suggests perplexity, as though he is grappling with some insoluble problem but determined to battle his way through it nevertheless. Part of this is no doubt nerves, and the pressure that comes with that need to nail down your place in the side. The England bowlers know this, getting in his ear at the earliest opportunity to try to unsettle him.

Then, someone will serve him up a bad ball and the boundaries will start coming and the confidence will start growing. Straight balls will be clipped off the pads; balls outside off-stump will be left alone or pulled to the midwicket boundary, as he starts using his bulk and his slight tendency to lean towards the off-side to his advantage. His physical strength becomes less a leaden weight than a battering ram.

By the time he went to tea on 95, the transformation was complete. Stuart Broad and Steven Finn could only look on in despair, and it’s to Jimmy Anderson’s immense credit that he managed to sustain the aggression with which he ran in on a wicket that gave him nothing. Monty Panesar too, came in for some fearful stick from both Fulton and Williamson, and earlier on from Rutherford, who was the only wicket to fall all day.

I wondered what was going through Fulton’s mind as he approached his maiden Test century. He’s been around the game for a long time. Prior to this, his highest Test score had come in his second match, against the West Indies at the Basin Reserve back in March 2006. He made 75 that day, and lost his wicket with – yep, you guessed it – a prod outside off-stump, feet going nowhere, an outside edge snaffled by the keeper. But all that seemed behind him now. Wiping the sweat from his eyes, forced to wait nine balls on 99, he could be forgiven for looking a little nervous now that that long wait could be about to end. End it did, with a scampered single off Panesar, and a pumped fist in celebration. Whatever the nature of that insoluble problem, maybe this innings will have provided the answer.

Alastair Cook made the same mistake as Brendon McCullum did at Wellington in choosing to bowl first – he was tempted by the siren call of a wicket that was supposed to seam but didn’t; that was supposed to offer more bounce for his quicks but instead gave them deliveries that, even with the new ball in the evening session, died on their way through to the keeper. The only spin on offer was that employed by Steven Finn who reckoned afterwards England had done a good job in “only” allowing New Zealand to put 250 runs on the board in perfect batting conditions. As an attempt to take the positives from a long, frustrating day, it was a pretty desperate one.

Fulton and Williamson’s partnership is currently worth 171; Williamson will resume on 83, Fulton on 124.

It took an earthquake in 226 BC to finally topple the Colossus of Rhodes. With Peter Fulton, it could easily be another ill-advised waft outside off-stump. Until then, and against all expectation, this is one giant who so far has managed to stand firm.

Thursday, March 21st, 2013

Two Tests, two draws.

There’s something almost reassuring in an England series being ruined by rain, regardless of where in the world they might be playing. Truly, England bring their weather with them.

The first Test was one England managed not to lose, and in the second they were prevented from winning by the obdurate steadfastness of Kane Williamson and Ross Taylor’s third-wicket stand, an 81-run partnership that was unbroken when rain stopped play, much to England’s frustration.

Both sides are bullish going into the final Test at Auckland’s Eden Park tonight. It’ll reflect well on the fighting qualities of Brendon McCullum’s men should this too end in a draw, but it would be a definite blow for England’s pride with an Ashes summer ahead – regardless of the disarray Australia are in right now.

Kevin Pietersen has flown home with a knee injury – Jonny Bairstow is expected to play at 5 or 6 while Ian Bell will be pushed up the order to bat at 4 – and a fresh pair of legs for the home side will come in in the form of Doug Bracewell, recovered from his foot injury. While the 0-0 score gives the impression of parity, in truth England have had only one bad innings so far; signs are that, having got that particular nervous tic out of their system, it is back to business as usual for the former number-one Test side. This impression was reinforced by Stuart Broad battling through a heel niggle and a recent run of poor form to take 6-51 in New Zealand’s first innings at the Basin Reserve before England enforced the follow on. It was a feat Lazarus could be proud of, were he a fast bowler before he took a bit poorly.

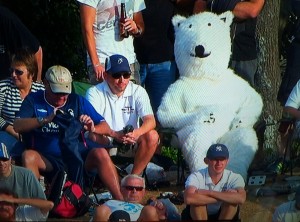

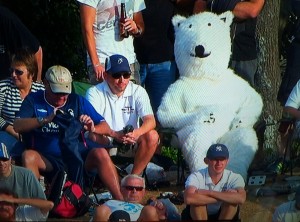

Speaking of signs and portents – maybe it’s because I’ve been watching Vladimir Bortko’s excellent television adaptation of Mikhail Bulgakov’s Master and Margarita recently, but I was slightly perturbed when this popped up on my TV screen:

Instead of a large black cat signalling the advent of satanic shenanigans in Stalin’s Moscow, I like to think of this chap as an unwitting harbinger of extreme weather conditions, given that Cyclone Sandra swept in the next day, breaking the longest drought in New Zealand’s history since 1947. With all the talk being of flat wickets which don’t break up and have offered little for the bowlers, at least it’s kept things interesting in terms of the overall series result. But gods, it looked miserable for the spectators, cowering under their umbrellas on that last day as they waited for play to be called off. But for the slightly more picturesque surroundings, it could have been Grace Road in April.

Thankfully, the forecast for Auckland is for five days of sun.

Wednesday, March 13th, 2013

Calling it a winning draw, in the words of Simon Doull on commentary, might have been stretching it a little, but England managed to at least salvage their self-respect at Dunedin after a diabolical start.

Their 167 all out represented the fourth consecutive occasion they’ve scored less than 200 in the first innings in the opening match of a Test series on foreign soil. Like lemmings proceeding in single file off a cliff; or a man standing on the edge of a subway platform who feels the irrational urge to jump though every ounce of reason or logic tells him not to; that or first-day-back-at-school recklessness; it’s almost something England feel they have to get out of their system nowadays before buckling down in the second innings and showing us what we know they’re capable of.

Only Jonathan Trott showed the application that was necessary, and if there were any lingering doubts as to the fact the pitch had no demons in it whatsoever, Hamish Rutherford quickly dispelled them as he made the most of the benign conditions with an assured and confident 171 on debut. Whether or not he’d find batting as easy on a subcontinental turner, or a truly green seamer, as he made it look here remains to be seen, but that’s not to take anything away from a knock that was impressive in its strokeplay and maturity. This lad’s got a future.

England may have regained their self-esteem thanks to second-dig centuries from Cook and Compton, and the heretofore-unrevealed talents of Steven Finn as an all-rounder, out lbw for 56, to ensure the draw. But watching that contagion of collapse that swept through their first innings like the batting equivalent of Spanish flu, one can’t help but wish England would rid themselves of this alarming psychological glitch.

Thankfully, on past record, this is unlikely to happen in the second Test at Wellington, which starts tonight. At the very least this should be a more equal contest between bat and ball, the pitch at Dunedin proving so moribund as to kill off any chance of a result once the first day was lost to rain. The Wellington wicket will have more in it for the seamers, something that could present a conundrum for New Zealand should they win the toss: bowling first could bring dividends, but Brendon McCullum’s doughty posse of hard-working quicks, who gave their all so wholeheartedly in the first Test – Neil Wagner deserves special mention – may yet be a bit stiff in the legs after their heroic exertions.

If England have a devil on their shoulder urging them to bat like idiots in the first innings of a first Test abroad, Australia have already pushed the self-destruct button, and we’re all standing back and marvelling at the mushroom cloud.

The suspension of four players ahead of the Mohali Test – James Pattinson, Mitchell Johnson, Usman Khawaja and vice-captain Shane Watson – for failing to complete a written self-assessment after the drubbing they received at Hyderabad has provoked much hilarity on Twitter and, elsewhere, more serious examinations of the sport’s growing professionalism and how this needs to be reflected in “team culture”. Coach Mickey Arthur has said this represents the culmination of “lots of small minor indiscretions that have built up to now… Being late for a meeting, high skin folds, wearing the wrong attire, backchat or giving attitude are just some examples of these behavioural issues that have been addressed discreetly but continue to happen”. He has the full backing of captain Michael Clarke, who referred to “a number of issues on this tour where I don’t think we have been hitting our standards”.

Ultimately, though, this whole shemozzle has been exposed to the glare of public hilarity and derision through four cricketers’ refusal to turn in their homework on time. More seriously for Australian cricket, it exposes the fact that there isn’t a heck of a lot of respect for coach and captain amongst the squad, and that if management are going off the deep end over paperwork, then, like a school teacher screaming hysterically at a classroom full of unruly six year olds, it’s plain they’ve already lost control. With all the talk over Clarke’s at-times tense relationships with players under his watch, past and present, it also shows up the mythical Aussie concept of “mateship” to be just that – a myth. How Australia pull themselves together after this, to the extent where their focus falls once again on the sport’s basic concepts – scoring runs and taking wickets instead of assignments and “wellness forms” – remains to be seen.

Meanwhile, England will be looking to press the reset button in Wellington while licking their lips in anticipation of an Ashes contest that’s looking increasingly like going their way with every day that passes.

Tuesday, March 5th, 2013

England begin their Test series against New Zealand in a few hours’ time. A New Zealand XI have already beaten them in the recent four-day warm-up match at Queenstown, but the noises coming out of the England camp are those of caution, rather than dismay. England, after all, may have had an indifferent 2012, losing their number one status to South Africa, but they capped off their winter with a surprisingly dominant series victory on the subcontinent against India, and having already beaten New Zealand in the T20s and ODIs, the upcoming three Tests comprise a series England are widely expected to win.

But I’m hoping that, as the Kiwis failed to consistently challenge in those shorter formats conventional wisdom tells us they’re more comfortable in, so they may surprise us in the longer version and maybe shove a spanner or two in the works of the England machine.

It would be one hell of a surprise, admittedly – but anything is possible. If there’s one memory of the late Christopher Martin Jenkins that springs immediately to mind, it was the sound of his dolorous tones on a digital radio under the blankets at 2AM on a cold March night back in 2008 as England, set a target of 300 to win, were bowled out for 110 in the first Test at Hamilton. England did pull themselves together and go on to win the remaining two Tests and the series, but nevertheless that Hamilton hammering was an unpleasant wake-up call; England were timid, clueless, and undercooked. “This is awful,” CMJ pronounced as wickets fell with alarming frequency. It was the voice of a man shocked to the core. Had wickets and runs not been involved, one could imagine this tone reserved for the reading out of a casualty list from a foreign battlefield. Marathon, possibly.

Sadly, though – on paper, on the field, whichever way you look at it – New Zealand are the obvious underdogs. Warrior spirit will only take you so far, and there have been too many off-field distractions in the way of player-management showdowns and gifted and promising players being struck down by injury, from the unfortunate but prosaic, such as Martin Guptill’s hamstring strain, to the just plain daft, with Doug Bracewell suffering a cut foot while sweeping up broken glass after a fairly energetic party. Mind your step chez Bracewell, particularly if you’ve had a few.

Of course the real unwanted guest at this party will be the memory of New Zealand’s recent comprehensive demolition at the hands of a rampant South Africa. 45 all out may not plumb quite the same depths of their 26 all out against England back in 1955, but it’s the elephant in the room that New Zealand fans, and those who want a close-fought competition, can’t ignore. The gap in performance between the two sides at Cape Town and Port Elizabeth was glaringly apparent; as mismatches go, that series was the cricketing equivalent of Manchester United versus Shepshed Dynamo.

It’s provoked a lot of debate recently about the current pool of Test nations and whether some members deserve to be there. The idea of a two-tier structure isn’t new – back in 2009, Dave Richardson, then ICC’s general manager for cricket, suggested that Tests fought between sides of comparable ability would provide more closely fought contests, and safeguard viewing figures and attendance: “Ideally, you want to have the top teams playing against each other, and then teams of lesser standing playing against each other, maybe in a second division or a lesser competition such as the Intercontinental Cup. I think that’s the challenge for the ICC, that it can create some sort of context for Test cricket both at the higher level and at levels below that.”

Former England captain Michael Vaughan has said pretty much the same thing, mainly as a way of ensuring against a player exodus to the IPL and other T20 tournaments, especially if there is a financial incentive for reaching the top tier.

I’m sceptical, though, and to be honest, to me that’s not what the sport is about. Ghettoizing weaker nations in a lower division won’t create an incentive for players to turn out for their country if they’re only likely to face lowly opposition, and since the countries in the lower table would likely be those already strapped financially, it’s hard to see how they could develop substantially enough for promotion without some kind of outside assistance. For players from these nations, the life of a freelance T20 specialist will look infinitely more appealing, and in the short term, financially more rewarding, which seems counterproductive to what Vaughan is suggesting.

The gap between the top and bottom-ranked nations wouldn’t incentivise the weaker nations – it’d just turn the current divide into a yawning chasm.

New Zealand cricket may be at a low ebb just now, but playing against teams of comparable ability when you are a low ebb means you will likely plateau at that level, not rise above it. Should you manage to fight your way up and win promotion to the top division, the challenge to stay there might prove insurmountable. There is absolutely nothing to be gained by this in terms of development. Home series against England, India and Australia are big money spinners for New Zealand cricket. Fans want to watch the best players, those overseas stars who wear their aura like a mantle and whose great deeds precede them, and part of the romance of the game – in fact of all sport – is the hope that the home side manages to overcome the odds and make history of its own. These concerns don’t just apply to New Zealand: because everything is cyclical, what’s to say England couldn’t return to the bad old days of the nineties and find themselves relegated to the second tier, with Australia in the top? What would happen to the Ashes then, with a divisional divide between them?

New Zealand Cricket recently received an ICC handout of $2.14 million, which will be put towards development in coaching and their “A” tours programme. There may be a few New Zealand fans and pundits who bridle slightly at what they see as charity, but this is how it should work – the sport looking after its own, the family of Test nations rallying around each other. (There are, of course, those who could be doing more in this direction – that India may be looking to trim New Zealand’s tour early next year in order to host the Asia Cup doesn’t do much to banish the impression that the weaker nations are already seen as expendable.)

Underdogs may lack pedigree, but that doesn’t mean they should be packed off to a Division 2 homeless shelter, subsisting on their own meagre resources and gazing on in envy at their richer cousins even as the latter look down on them in lofty scorn from the high table of Division 1.

The road to the top’s already a hard one. For those in Division 2, just getting themselves onto that road could prove a test too far.

|

|