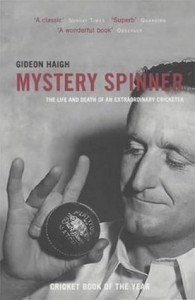

Book review: Mystery Spinner by Gideon Haigh

It took me three weeks to read Gideon Haigh’s Mystery Spinner, but I do have a good excuse.

I started it on an outbound flight to Melbourne three weeks ago and, as you can imagine, subsequent events kind of demanded my full attention from then on.

Back in Blighty, with the Ashes retained and a series won, I was finally able to give it my undivided attention. This would mostly occur at 3AM, in short bursts of intense reading, mind awake and alert, body fighting through the weighty sludge of jet-lag and a final 48 hours of my trip with no sleep.

I am sure this added to the experience. Not many folks are awake in the early hours of the morning, save for new parents, serial killers, and Margaret Thatcher. Depressives, too: 4:48AM is supposed to be the time at which most suicides occur.

Jack Iverson did not take his own life at 4:48AM. He died from a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head during the afternoon of Tuesday, 23rd October, 1973, in the shed at the rear of his house.

It was a lonely end to the life of an ordinary man who had a brief but extraordinary cricket career, a man who is little remembered now but who was, for the duration of most of his short career, feared by batsmen and deemed unplayable.

Iverson was a one-off, a freak. He honed his remarkable thumb and middle finger grip with a table-tennis ball before taking up French cricket while stationed at Port Moresby in New Guinea as part of the Australian Imperial Force. He ended up playing for Victoria, winning the Ashes for his country at the Sydney Test of 1951 with a haul of 6 wickets for 27 runs.

He played in only 5 Tests, but when he retired it was with the remarkable figures of 21 wickets at 15.23.

His career was plagued by at-times crippling self-doubt and pressure from a father who wanted his son to carry on the family real estate business. Iverson voiced his first thoughts of retirement after playing in only his first Test, and lived in fear of “being found out”, that he just wasn’t good enough.

Shy, inward looking, personable but not extrovert, he was diagnosed in 1968 with depression, exacerbated, Haigh postulates, by cerebral arteriosclerosis, a narrowing of blood vessels to the brain. He was given electroconvulsive therapy and anti-depressants, which he sometimes refused to take in the belief that they were not working.

With those who suffer depression, small disappointments can often seem catastrophic. Iverson’s wife described to police that on the day her husband killed himself that she had found him sitting in the lounge room “upset and shaking visibly”. He had learned that the man to whom he had sold his real estate company had not adhered to a previously agreed financial arrangement and that he was owed commission on the sale of a house.

After apparently calming down, he went out the back to the shed. Mrs Iverson began vacuuming, and so did not hear the shot that killed him.

Because Iverson’s career was so short, Haigh found he task of researching his life sometimes a difficult one.

‘The man who lived “in my own quiet way” left little behind; no published works, no journals, no boxes of correspondence, only some photos, statistics, reportage of his feats and a scattering of others’ recollections. As I traced his fugitive figure, I often learned more than I had expected, but less than I wanted.’

This book put me in mind several times of Ian Hamilton’s In Search of JD Salinger, in that, as in the case of Hamilton’s famously reclusive subject, Mystery Spinner is as much a meta-biography, the story of a writing of a biography, as much as it is a biography itself.

There is necessarily some padding – Haigh devotes 35 pages to a history of bowling in general and spin bowling in particular, but this is a minor quibble, and it does place Iverson’s abilities and achievements in context.

He also makes the point that because Iverson came late to the game, he arrived on the international stage with a fully-formed technique developed and untampered with by the meddling of coaches – a single-minded auto-didacticism shared with other greats of the game, such as Trumper, Bradman, and O’Reilly.

In the end, I suppose the question is, how much can we really know about a man from his achievements in the sporting arena?

With some, such as Victor Trumper, their greatness outlives them to such an extent that some details of their lives inevitably become subject to embellishment or exaggeration.

In Jack Iverson’s case, his grip on a cricket ball is more familiar than his face.

Haigh treats his subject with sensitivity and respect, and the result is a work which succeeds admirably, not just on the level of biography, but in the treatment of a uniquely talented but deeply troubled individual who, for an all-too-brief period, made cricket history.

Mystery Spinner, by Gideon Haigh, Aurum Press 2002.